December 24, 1931 Gorebridge, Scotland

I was born on Christmas Eve in a small Scottish mining town where my father was the Presbyterian minister. When the doctor’s wife heard that the baby was on the way, she gave her husband an early Christmas present. When he opened it, he found a miner’s lamp that he could strap to his head and use in houses that didn’t have electricity. So that’s how it happened that I came into the world on Christmas Eve my eyes not dazzled by a holy star, but by the beam of a miner’s lamp.

1939 to 1945 We now live in Lockerbie in southwest Scotland. Britain is

engaged in World War II.

A lot of my childhood memories center on the freedom we had back then to

wander through the fields and woods close to our house. One of our favorite

places to play was The Boggy Bit, a stretch of wasteland that someone had

started to drain, but had given up on. It was scored by a large number of

parallel ditches, which disappeared into a marsh. Peter, Ann and I spent

hours there, catching

minnows, sticklebacks and tadpoles, and picking wildflowers. Against our

garden wall was an old washhouse that hadn’t been used for years.

We turned it into a museum, where we displayed moldering collections of

insects and pressed flowers and a sheep’s skull we’d found in

the Boggy Bit. The sinks were great for rearing tadpoles and keeping snails.

catching

minnows, sticklebacks and tadpoles, and picking wildflowers. Against our

garden wall was an old washhouse that hadn’t been used for years.

We turned it into a museum, where we displayed moldering collections of

insects and pressed flowers and a sheep’s skull we’d found in

the Boggy Bit. The sinks were great for rearing tadpoles and keeping snails.

One summer we mapped the Boggy Bit, naming every ditch and plank bridge, and made up involved adventure stories about the imaginary inhabitants of our land. Perhaps that piece of marshy ground provided the crossover between nature study and fiction that eventually led me to write both science books and fantasy. They weren’t far removed from one another in The Boggy Bit.

When Ann started school, it fell to me to take her there each day. Ann did not enjoy the long walk up the Dumfries Road. One morning she sat down on the curb and refused to go any farther. That was fine for her because she had nice, gentle teacher, whereas I had Miss Walker who was a witch and gave us the cane if we were late. I was too conscientious to leave Ann sitting there, so I bribed her with a story. It was about a Tom-Thumb sized character that I called Flibberty Gibbet. Poor Flibberty had all sorts of adventures and mis-adventures. And I found that the more exciting the story was, the faster Ann would walk! The story lasted for years.

Early in the war we had evacuees living with us; city girls named Ruth and Rita, who were older and wiser and far more sophisticated than Ann and I. Even so, they liked listening to my stories. But they didn’t want to hear about Flibberty Gibbet. They wanted romance! That really stretched my imagination.

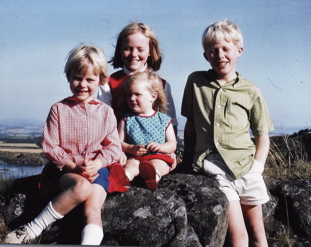

The 1960s. I now live in Corvallis, Oregon, with my husband Norm and our four children – Richard, Judith, Susan and Karen.

When the children were young, I was still telling stories. I

used them as a bribe to keep them from fighting in the car or out from under

my feet when I was ironing. Just the sound of me setting up the ironing board

and spitting on a hot iron brought them running from the farthest corner of

the house or yard.  They’d

plunk themselves down on the floor with shining upturned faces as if I were

a TV turned on to their favorite program. They especially like my “war

stories” which were more about my childhood than the war

They’d

plunk themselves down on the floor with shining upturned faces as if I were

a TV turned on to their favorite program. They especially like my “war

stories” which were more about my childhood than the war

With a husband and so many children the laundry basket was always full and I figured I’d be telling ironing stories forever. But then someone invented permanent press fabrics. Now Norm could take a clean shirt from the drier and bypass the whole ironing routine.

With so much extra time on my hands,  I

decided to take up writing.

I

decided to take up writing.

At first I wrote nonfiction. In the part of my life I haven’t had time

to tell you about, I studied biology and genetics at Edinburgh University.

Then I worked as a statistician. I met Norm at a biological research laboratory

in Canada.

The 1970s and 1980s

After writing magazine articles for Ranger Rick and Nature and Science, and a book on insects, I tried my hand at fiction. Writing stories isn’t as easy as telling them. For a start, there’s just me and the blank face of the computer screen which never gives a gasp of delight at a sudden new twist of the plot or begs for more when I’m ready to quit for the day.

A

lot of my early books were set in Scotland. Maybe I was a bit homesick for

my childhood home. Writing about the places I’d loved gave me the chance

to spend time there in my mind. This was especially true of In the Keep of

Time and the Circle of Time. Searching for Shona grew out of my ironing stories.

The Brain on Quartz Mountain and The Ghost Inside the Monitor and Olla-Piska

are Oregon stories -- though Olla-piska is a historical novel about David

Douglas. a Scottish botanist. So it covers both my favorite places. The cover

art is by Corvallis artist, Ellen Beier.

A

lot of my early books were set in Scotland. Maybe I was a bit homesick for

my childhood home. Writing about the places I’d loved gave me the chance

to spend time there in my mind. This was especially true of In the Keep of

Time and the Circle of Time. Searching for Shona grew out of my ironing stories.

The Brain on Quartz Mountain and The Ghost Inside the Monitor and Olla-Piska

are Oregon stories -- though Olla-piska is a historical novel about David

Douglas. a Scottish botanist. So it covers both my favorite places. The cover

art is by Corvallis artist, Ellen Beier.

The Druid’s Gift took me back to Scotland, or rather to

the St. Kilda Islands 112 miles west of Scotland.  The

St. Kilda way of life depended on the seabirds that nest on the spectacular

cliffs. Although the book is a fantasy, it is also about the history and legends

of the islanders. After it was finished, I took part in an archaeological

dig on St. Kilda. Not many authors get to visit their Fantasy Island! The

best part was that everything was exactly as I had known it would be. As I

watched the full moon floating over the rugged peaks of Dun, Caitlin and Tormod

Rudh were right there beside me.

The

St. Kilda way of life depended on the seabirds that nest on the spectacular

cliffs. Although the book is a fantasy, it is also about the history and legends

of the islanders. After it was finished, I took part in an archaeological

dig on St. Kilda. Not many authors get to visit their Fantasy Island! The

best part was that everything was exactly as I had known it would be. As I

watched the full moon floating over the rugged peaks of Dun, Caitlin and Tormod

Rudh were right there beside me.

The 1990s and up to the present day. I am still living in Oregon.

The

children are grown now and have children of their own. So I have a new audience

for my stories. “Tell me a Tom thumb story,” Gillian says as we

walk together from school. And my writing has gone the full circle. I’m

back where I started writing magazine articles, this time around for ASK magazine,

and nonfiction books. Biographies are very satisfying to write. I’ve

written about Charles Darwin, Isaac Newton, Carl Linnaeus and Aristotle. This

has given me the chance to get to know famous people really well.

The

children are grown now and have children of their own. So I have a new audience

for my stories. “Tell me a Tom thumb story,” Gillian says as we

walk together from school. And my writing has gone the full circle. I’m

back where I started writing magazine articles, this time around for ASK magazine,

and nonfiction books. Biographies are very satisfying to write. I’ve

written about Charles Darwin, Isaac Newton, Carl Linnaeus and Aristotle. This

has given me the chance to get to know famous people really well.

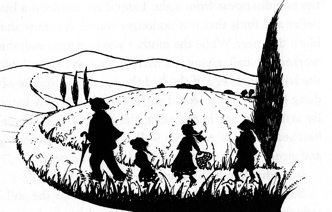

I’ve also written about not-quite-so-famous scientists, such as David Douglas and Henri Fabre. Fabre in Children of Summer is an eccentric entomologist. What was great about that book was that I worked with a gifted illustrator, Mari Le Glatin Keis.

Marie

and I traveled to France together to visit Fabre’s museum and some of

his old haunts. It was a happy journey and Marie introduced me to sketching.

Marie

and I traveled to France together to visit Fabre’s museum and some of

his old haunts. It was a happy journey and Marie introduced me to sketching.

I’ve used what I’ve learned about biology to write three Nature Discovery books. They were co-written with my daughter Karen Stephenson and publisher Nan Field. I’ve also done a couple of biographies with Karen (Scientists of the Ancient World and Aristotle) and have collaborated with archaeologist Gwinn Vivian on writing Chaco Canyon and with Pam Cressey on Alexandria, Virginia. Writing is rather a solitary occupation, so it was great having someone to talk to that always wanted to share ideas.

On

every article and book I’ve written from my very first (Exploring the

Insect World) I’ve had all sorts of help and encouragement from my husband

Norm. He’s an entomologist who dearly loves his “children of summer”

– that’s what Henri Fabre called his insects. Although Norm has

retired from Oregon State University, he still follows the life cycles of

the bugs that live in the streams that run through our property. I’ve

never written a book about Norm, but he’s been there in all of them.

On

every article and book I’ve written from my very first (Exploring the

Insect World) I’ve had all sorts of help and encouragement from my husband

Norm. He’s an entomologist who dearly loves his “children of summer”

– that’s what Henri Fabre called his insects. Although Norm has

retired from Oregon State University, he still follows the life cycles of

the bugs that live in the streams that run through our property. I’ve

never written a book about Norm, but he’s been there in all of them.

Sketches from Children of Summer used with permission

of the illustrator,

Mari le Glatin Keis

| Home Biography Publications Purchase Contact Webpage updated:

September 16, 2013

|